Remote, uninhabitable, captivating. This is how the Polar North is still imagined to be, even in today’s globalized consciousness. In the context of the international symposium “Representations of the West Nordic Isles. Greenland – Iceland – Faroe Islands”, an interdisciplinary group of researchers met at the Eutin State Library in Germany’s northernmost state of Schleswig-Holstein, to discuss how the Arctic isles were experienced and mediated between the 15th and 19th century. European travel documents show conceptualizations of the Polar North as a political target to be claimed, colonized and civilized, and to make use of its resources and geographical location. Descriptions range from outlandish desolation to sublime admiration, exhibiting surprising resemblance to contemporary travel records of these places.

The international conference gave me the opportunity to meet and discuss with travel studies scholars from all over Europe. Luckily, guests also included academics living and working on the islands that the conference was focusing on, such as scholars from the University of the Faroe Islands and the University of Island. Thus, the conference made it possible to gain insights into cultural and linguistic details of life on Arctic islands, and to contextualize historical notions of these places with contemporary facts.

Looking at different periodicals published during the middle of the nineteenth century, my own contribution to the symposium explored visual-verbal representations of the Polar North in Mid-Victorian Britain. These illustrated newspapers had a considerable influence in the perception of all places that were other. Since the Arctic lied beyond the grasp of modern communication, was neither reachable by telegraph nor by train, news of expeditions could not reach the public immediately, which prompted the press to get creative. They created intriguing semi-fictitious stories, comprised of information material from varied factual and fictional backgrounds, and often re-mediated these. These representations had the potential to influence a growing number of British subjects hungry for these heroic, often fatal accounts of an unworldly world.

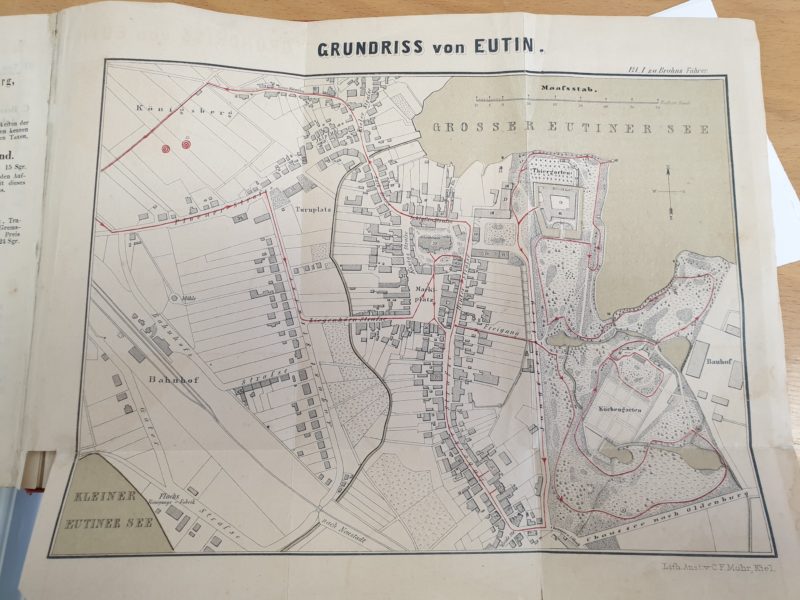

Eutin served as a beautiful setting for our academic discussions. Having already progressed well into the fall, East Holstein’s lakes, between two of which Eutin is picturesquely squeezed, emitted a peaceful and foggy presence. Because my visit to the North was also undertaken to prepare for my upcoming practical phase, I used the time after the conference to get acquainted with people from local tourism, cultural institutions and regional development. In the coming weeks, I will build a more concrete idea about how my time in Eutin next year will look like. Stay tuned!